- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

|

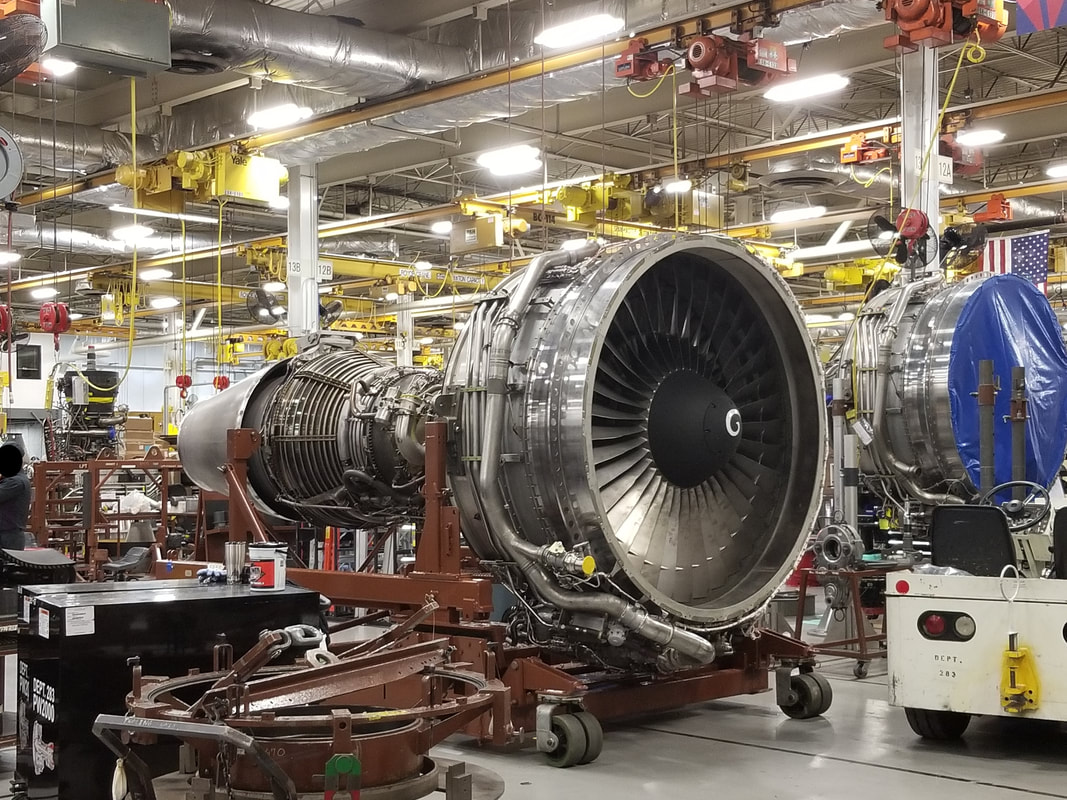

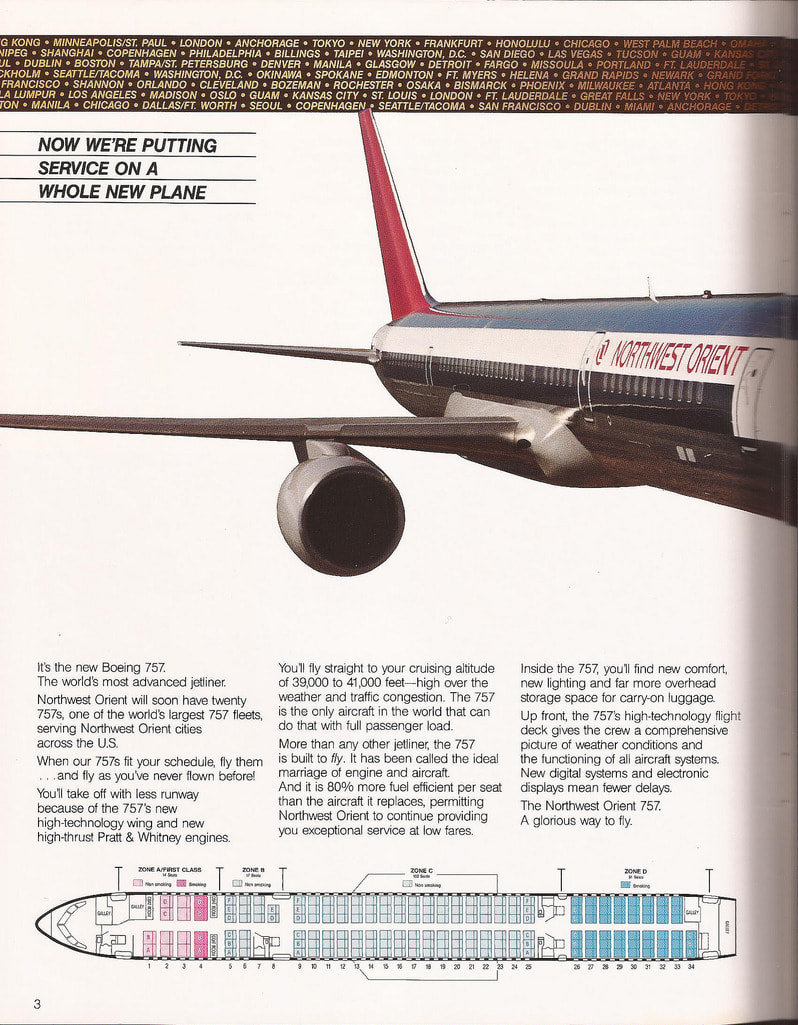

By the time the design of the new Boeing 757 was finalized in 1979 it was clear it would be a big improvement over the 727-200 Advanced and yet some commentators were under the impression that with both the 757 and 767 Boeing was effectively competing against itself as much as against the Airbus A310. Initially sales seemed to give this a grain of truth but eventually the 757 would find its time had come. For part 1 in this series see: Aside from doubts about the physical ability of Boeing to finance and manage two different aircraft production projects at the same time the 178-seat single aisle Boeing 757 was suspiciously close to the 210-seat twin aisle Boeing 767-200 in size. The drop-dead cancellation date for the 757 was October 11, 1979, well after the first orders were placed, when Boeing had to commit to over $1 billion in contracts for the fuselage sections from four sub-contractors. British Airways, Eastern Air Lines and Rolls-Royce stated that they were certain that the 757 would go ahead despite relatively lacklustre sales, and indeed McDonnell Douglas was waiting in the eves with its own Advanced Transport Medium Range project (ATMR) helping to force Boeing’s hand. New customers were nonetheless thin on the ground. Delta had not been a Boeing customer until the early 1970s – it actually inherited its first narrowbody Boeings when it tookover Northeast Airlines and its 727s. Before then it had only acquired a small number of 747s in 1970. Boeing showed its business acumen by actually assisting Delta to shed the 747s, when it found them too large, at no profit to itself. Part of the result of this was a major 116 aircraft order for 727s and of course Delta also became the launch customer for the 767. Delta was also in the frame for the new 757 and on November 12, 1980 it placed a huge 60 aircraft $3 billion order for the type, representing for Boeing the first large order since the type’s launch, and by far the biggest order as well. The Delta order was a major boost for Boeing and the credibility of the 757 as a whole. Engine choice was an area of intense competition within the 757 programme, which became the first Boeing product to launch with a foreign engine – the Rolls Royce RB-211-535C. Both Eastern and British Airways had chosen the Rolls engine partly because they both already used variants of it on their Lockheed Tristars. Two smaller customers, Transbrasil (who had ordered 3 plus 2 options) and Aloha Airlines (who had 3 unconfirmed orders), each chose the competing General Electric CF6-32C1, which weighed less than the Rolls option. Getting this engine option off the ground required a supplementary order from a major airline and despite allegedly putting in a ‘totally uneconomic offer’ in the battle for the engine rights for Delta’s 757s they failed to achieve a victory. In 1981 GE cancelled certification of the engine for the 757 and subsequently both Transbrasil and Aloha would cancel their 757s anyway. The third engine option came from Pratt & Whitney with their PW2037. Both they and Rolls Royce competed for the Delta order but Pratt won the competition partly by guaranteeing that its engine would outperform any Rolls engine by 8%. This was based on estimates and a dangerous game to play. It is said that Pratt didn’t think Rolls had a new engine. They must have been unhappy when Rolls produced the improved RB-211-535E4 engine in 1984. For three years, until the end of 1983, Boeing received barely any orders for the 757 at all. This was due to a combination of factors. The US economy had entered into recession whilst deregulation of the US airline marketplace had introduced competition that left many of the established airlines on the defensive. Airlines like United considered the 757 too large for their needs in an era when the majors were beginning to build large hubs based upon service frequency. This favoured smaller aircraft like the McDonnell Douglas DC-9 Super 80. Fuel prices had also dropped enabling older less efficient types like the DC-9 and 727 a new lease of life. Not only did this mean the majors were less keen to retire them but newer airlines could use the older cheaper types to compete more heavily as well. At the time of the first flight of the 757 in February 1982 orders for the 757-200 (the smaller 757-100 was dropped) totalled only 136 aircraft from 7 airlines: Air Florida, American Airlines, British Airways, Delta Air Lines, Eastern Air Lines, Monarch Airlines and Transbrasil. The economic downturn saw to the cancellation of the entirety of the orders from Air Florida, American Airlines and Transbrasil. Even British Airways wasn’t immune and two of its orders were transferred to the new British charter airline Air Europe. The first Pratt & Whitney PW2037 equipped 757 flew on March 14, 1984 and deliveries commenced to Delta on November 5. By then the new Rolls-Royce RB-211-535E4 was already in service having joined Monarch, with its first 757, in October. The new Rolls-Royce engine variant was more competitive with the PW2037 and also more reliable and quieter. Pratt would win some subsequent order battles (notably with Northwest) but in the end it would be the RB-211-535E4, which would dominate future orders. The order that brought the Boeing 757 back into the game was that of Northwest Airlines in November 1983, whose timing narrowly averted an expensive decrease in the production rate. The order was for 20 frames at an estimated $800 million with the type allowing Northwest to improve efficiency and expand its growing hub operations. The type was especially suited to Northwest’s long domestic routes such as Seattle to New York and Washington. Northwest received its first 757-251 on February 28, 1985. Before it had received its 20th it had also received 6 more from its acquisition of Republic Airlines. As the US economy picked up the 757s natural qualities in terms of payload and range began to become more attractive, whilst noise regulations and increasing fuel costs also assisted it in acquiring sales. Large orders from the US majors, now coming out the other side of the most damaging period of deregulation, meant that American, Continental and United became major 757 operators whilst Delta and Northwest both swelled their fleets of the type with follow on orders. Northwest would operate 56 757-251s as well as 16 757-351s. Delta would fly 113 757-232s. Although Boeing’s optimistic sales predictions of 1,000 within the first decade did not come to pass by 1990 there was an order backlog of 400 units and the period from 1990 to 1994 saw peak production of 757s with 77, 81, 98, 71 and 69 aircraft produced respectively. The 757 weathered its initial troubles to fully validate Boeing’s faith in it and even today there is continuing debate as to which aircraft can fully replace the graceful Boeing. References

1983. Making it Fly: the Boeing 757. Seattle Times Boeing: Plane Makers of Distinction. Boeing 757. Wikipedia

4 Comments

23/5/2021 01:27:55 pm

how much does it cost for a rools royce engine on a 757-300

Reply

William J Baillie

1/5/2022 08:00:32 am

Who would be interested in one of the rarest 1/400th aircraft? It's an Eastern Airlines black box concord? Last one sold on eBay for 400 dollars and that was almost 4 years ago. If anyone is interested contact me Bill at 612 -704-7602. [email protected]

Reply

William J Baillie

1/5/2022 07:52:03 am

Ah, I've got one you don't have in your fleet and it should be. It's the chrome body Northwest Orient cargo 747 made by true to scale. I'm almost positive these were made for just employees. My name is Bill contact me if interested. Model neaver handled and in box it came in.612-704-7602

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm Richard Stretton: a fan of classic airliners and airlines who enjoys exploring their history through my collection of die-cast airliners. If you enjoy the site please donate whatever you can to help keep it running: Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed