The Plane that Almost Killed a Legend: Pan Am & the 747

This is part two of a series covering the early years of the Boeing 747. For part 1 see:

This post is dedicated to Richard W. Lee, a long time supporter of the site who donated the wonderful prototype Boeing 747 model to my collection.

Pan Am Starts to Bleed

As discussed in part 1 it was Juan Trippe's Pan Am that launched the Boeing 747 and Pan Am that first put it into revenue service, but it wasn't Juan Trippe's Pan Am by then as he had stepped down from his position as Chief Executive and Chairman of the Board on May 7, 1968. The acquisition of 25 747s was one of his last major decisions and it would prove to be a massive mistake at an airline that was already entering a period of massive financial troubles.

At the same annual stockholders meeting where Trippe announced his retirement Pan Am announced impressive figures for 1967. They had made a $65.7 million profit on revenues of $950 million, but things weren't as rosy as they appeared. Profits were down 21.5% and the first quarter of 1968 was showing operating costs outstripping revenue. The continuing massive year on year growth of air travel was beginning to slow down as economic performance decreased. Considering the airline wasn't filling its existing 707s the advent of a massive fleet of new much larger 747s was ominous.

|

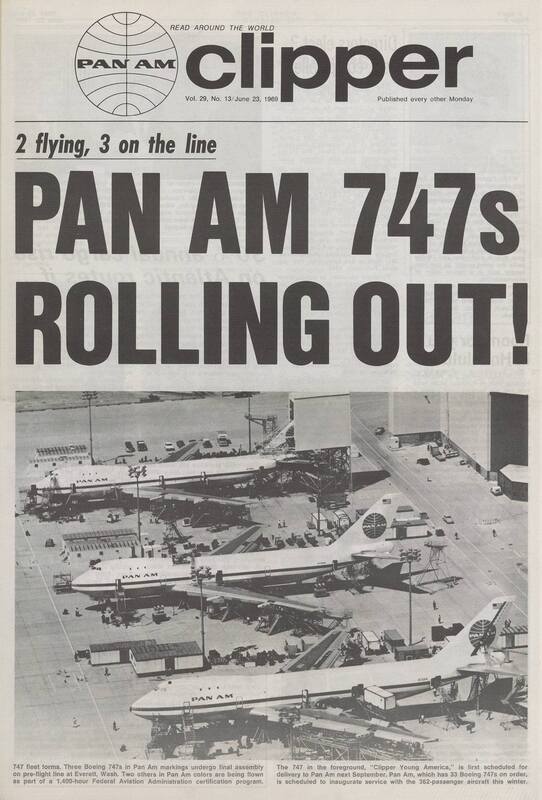

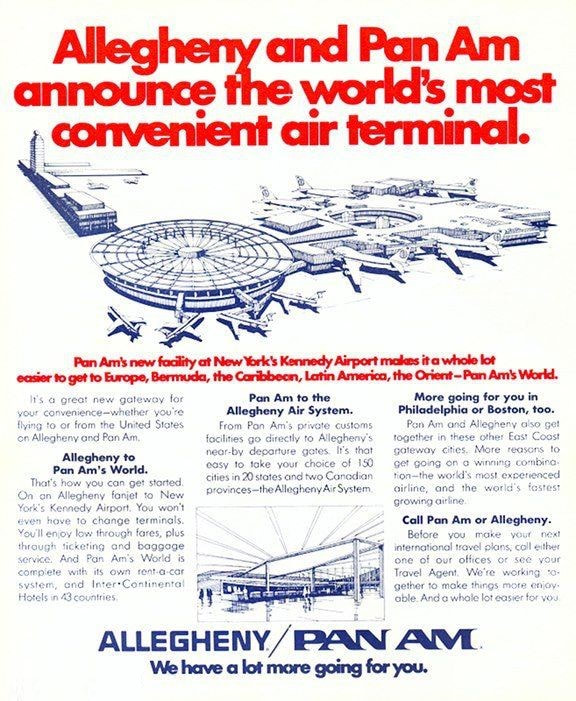

Pan Am had orders for 25 747s and options for a further 8. The options would cost a further $175 million. They weren't the only 747 related expenses. Pan Am's terminal at New York JFK would need to be rebuilt into the new Worldport to cater for the jumbos costing $126 million. On top of that Pan Am needed a 747 maintenance facility, also at JFK, costing another $98 million. Even with the worsening economic situation both Gray and Halaby thought the enormous expenditure made sense. Pan Am increased its order to 33 aircraft and went ahead with the new construction. This was in 1968 - the same year when earnings went down by nearly 19%. Things would only get worse and in the first half of 1969 a loss of $12.7 million was recorded. For the first time in 30 years no dividend was paid out at the end of the second quarter.

|

These weren't Pan Am's only problems. The carrier had a massive ego problem fed by its years of supremacy. The engrained culture made change extremely difficult, even to the extent of Trippe's replacement. Not that Trippe really left, he just moved his office down the hall! Given the immense power that Trippe wielded it was always likely that his departure would lead to problems, some fuelled by him still hanging around. Trippe's immediate successor Harold Gray was a stalwart company man, but his new President, Najeeb Halaby, was not. He was primarily a lobbyist, not the kind of person the highly conservative Pan Am employees or executives thought knew how to run an airline.

This shouldn't have been a major problem but it swiftly became one as unknown to everyone Gray had been diagnosed with a virulent cancer. By November 1969 he was forced to step down and Najeeb Halaby was thrust into the position of leading Pan Am. A position he was neither equipped for or that the old guard at the airline would accept him undertaking. By then, if anything, Gray had made Pan Am's future worse and it was the Jumbo again that did it.

|

Problems Everywhere

It wasn't just the leadership issues, hidebound management and a faltering economy that were at the root of Pan Am's growing malaise. Pan Am's network was also under siege from every angle. Competition from foreign national airlines was growing, no doubt especially so from recently reborn airlines like Lufthansa and Japan Air Lines, and more Americans were choosing to fly with non-US airlines. However, this was less of a problem than two other sources of competition - the previously primarily domestic US Trunk airlines, and a range of non-scheduled charter operators flying mainly across the Atlantic.

For years Pan Am had been the USA's chosen instrument, however in doing so Trippe's airline had run roughshod over Washington and made many enemies. Whereas all the Trunk airlines had powerful advocates in US politics, usually from their home states, Pan Am had few friends. It didn't help that it was based in New York, along with many other major companies giving New York no incentive to act on its behalf. The result was increasing inroads into Pan Am's international networks by US trunk airlines that had powerful US domestic networks to back them up.

|

Until the 1960s, and the Presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson, Pan Am had to deal with only one competitor in each of its major markets - TWA in the Atlantic, Northwest in the Pacific and Braniff in Latin America. With Johnson things became highly political and came to a head with the 1968 Transpacific Route Case. In an election year it became a frenzy of favour buying and debt paying with a highly partisan figure at the head of the CAB. Gray had no interest in this sort of thing, he was a straight shooter, but Trippe advised him to send Halaby to Washington to do some lobbying.

Halaby went, but it did no good. The eventual awards by the Johnson White House were a disaster for Pan Am. With the decisions not finalised before Nixon took office there was hope Pan Am might yet benefit but it was not to be. If anything Nixon was even more partisan. All of a sudden Pan Am faced a raft of new competitors flying to Hawaii and extensive Pacific route awards for American, TWA and Flying Tigers. This increasing competition on its international routes would fuel losses at the airline and Pan Am's desire for its own domestic network, a desire that would eventually lead it into the disastrous purchase of National Airlines.

|

Pan Am 747 Cabins & Configuration

While researching this article I came across this pair of impressive posts on Airliners.net, which covers in great detail the onboard experience of Pan Am's 747s and saves me having to write about it. Take a look here:

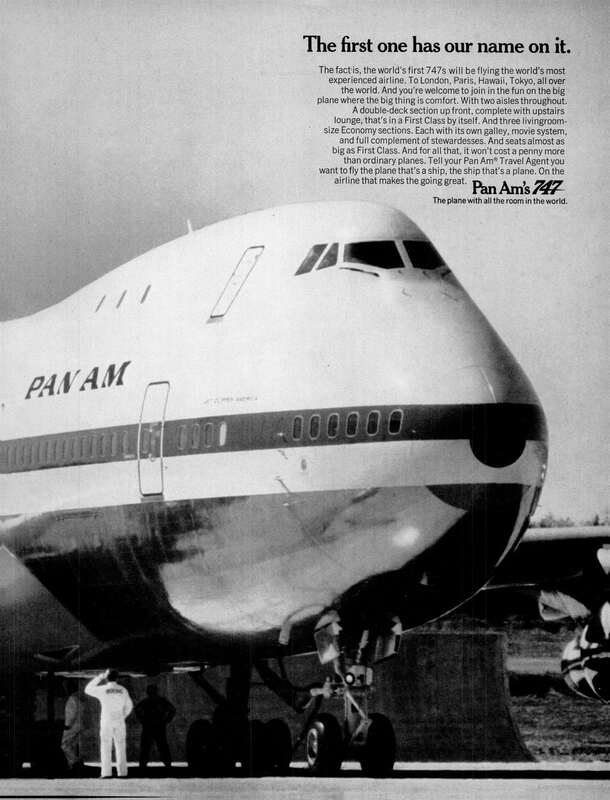

1970 - The 747 Makes Things Worse

By the time the Boeing 747 entered service with Pan Am in January 1970 the USA and Europe were in recession. The extravagant traffic growth required to compensate for the size of the 747s had evaporated. Pan Am was in serious trouble. It was losing money hand over fist, had huge debt from the 747 costs and was being attacked by competition from all sides. Various attempts to merge with other US trunk airlines including TWA, which had domestic networks, failed for various reasons - not least the intransigence of the Nixon White House.

The 747s themselves weren't helping matters. Not only were they flying around with thousands of empty seats but the reliability of the all new Pratt & Whitney JT9D engines was poor. The engine had a major stall problem, one that all too often led to a loud bang and sheets of flame exiting from the engine. The delays and cancellations caused by the engine troubles were costing $2.5 million more a month on top of the already $10 million monthly 747 costs.

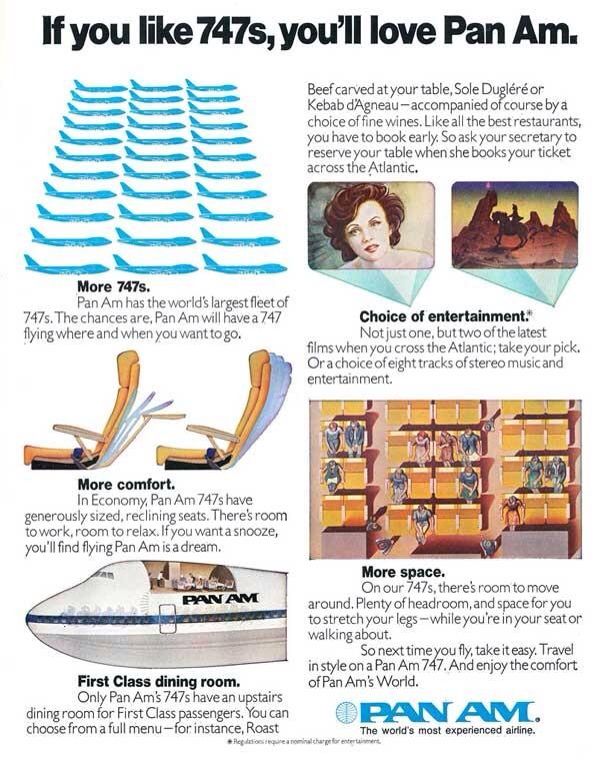

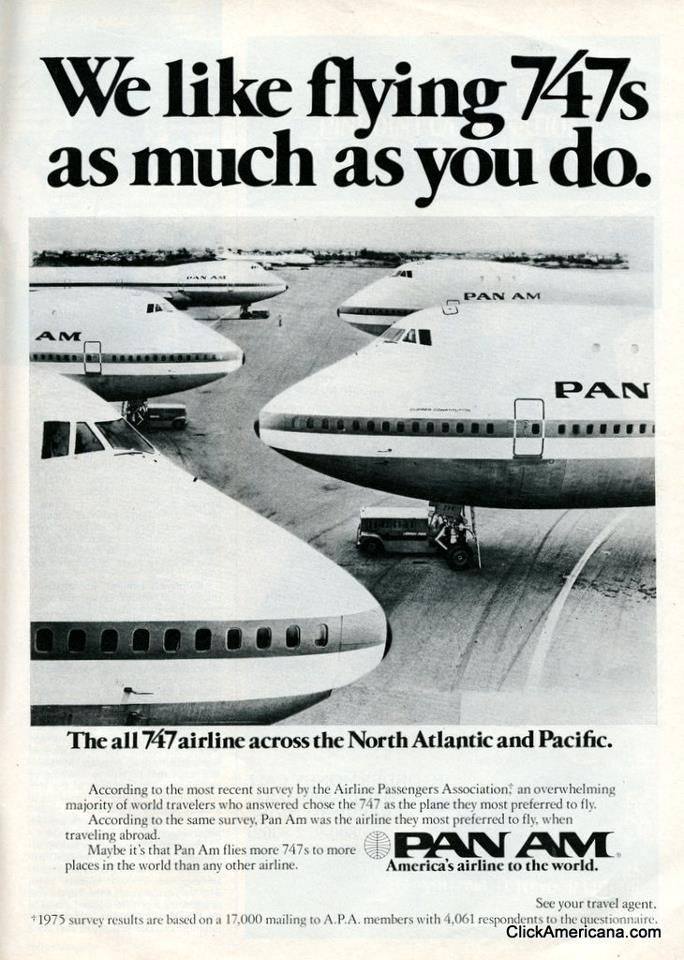

The first 25 747-100s were all delivered by the end of August 1970 and were put into service across the Atlantic from New York to Amsterdam, Barcelona, Brussels, Frankfurt, Lisbon, London, Paris and Rome, plus Chicago to London and Frankfurt, Washington to London, and Boston to London. They were also used on the polar routes from San Francisco and Los Angeles to London and Paris. In the Pacific they flew Los Angeles and San Francisco to Honolulu, Tokyo and Hong Kong. Lastly they also flew New York to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

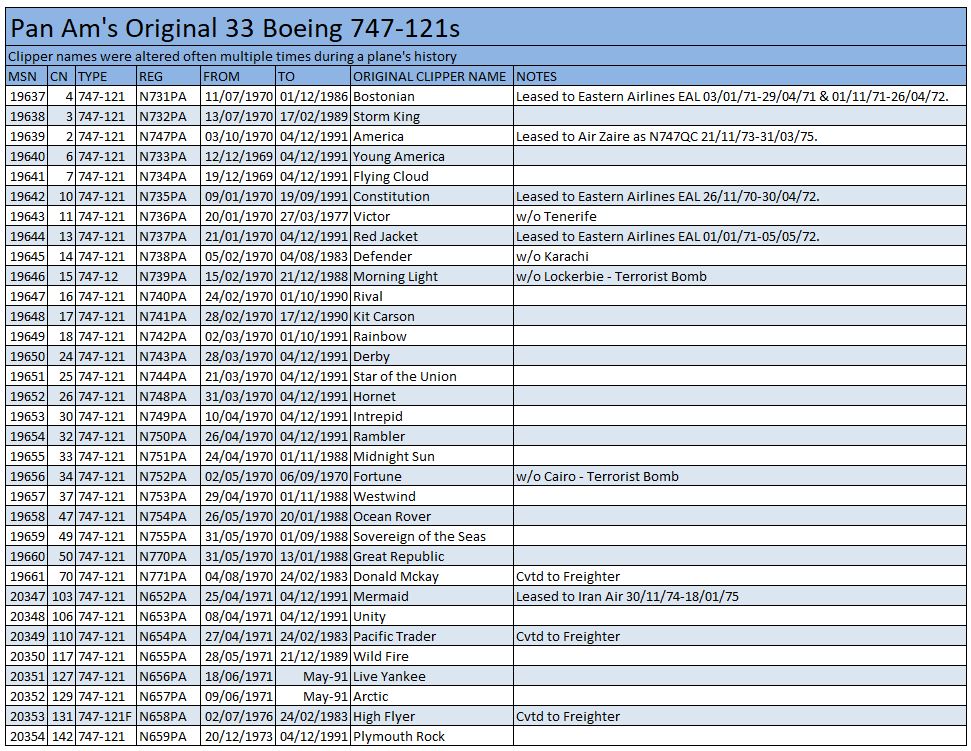

Clipper Names

Pan Am confusingly often changed the clipper names on the 747s, seemingly at random and annoyingly reused the same name on different frames at different times. This makes getting the name right a challenge and causes confusion even about obvious things like first flight. For example everyone knows the first revenue flight was by Clipper Young America but that was N736PA (originally and subsequently Clipper Victor) and not the aircraft it was meant to be N735PA (also Clipper Young America). However N735PA was originally Clipper Constitution and N733PA, the first 747 delivered, was originally Clipper Young America! Even worse N733PA was renamed Clipper Constitution (and later Clipper Washington and then Clipper Pride of the Sea).

It was N735PA, the original choice for first passenger service, that suffered the 747's first hijacking when on a flight to San Juan in August 1970 it was forced to make an unscheduled stop in Cuba. Worse N752PA was destroyed in a terrorist bombing in September 1970 after being forced to divert to Cairo when flying Amsterdam to New York. Palestinian Arab guerillas blew the aircraft up on the ground as part of a wider terrorist event - see Dawson's Field Hijackings. At the time of its destruction N752PA had only logged 1125 hours and was only four months old. Tellingly when hijacked it was only carrying 152 passengers.

In 1971 Pan Am lost another $45.5 million taking total losses over the previous three years to $120.3 million. The airline had debts of over $1 billion and the $270 million revolving credit for the 747 purchase was coming up for renegotiation in March 1972. The result of all these issues, most outside his control, led to Halaby being ousted by the board, partly at the bidding of Trippe himself.

Respite

Halaby's successor, the angry and tough General William T. Seawell, undertook a massive cost cutting exercise and the airline just about survived the Arab oil embargo and resulting fuel price shock of 1973, but still found little assistance from Washington. By October 1975 bankruptcy was looking likely but Seawell narrowly averted it by persuading Pan Am's creditors to take more 747s as collateral.

An employee led movement nicknamed AWARE had also raised Pan Am's profile in Washington and when in 1974 Pan Am and TWA appealed for a significant realignment of their route networks, whereby they would swap services with each other to cut competition, it was approved by the CAB in early 1975. The details of the arrangement were:

"TWA gave up it's worldwide services, meaning it stopped service to Honolulu, Guam, Okinawa, Taipei, Hong Kong, Bangkok and Bombay. Also TWA gave up all services to Frankfurt. In addition service to London was suspended from IAD and limited through services from SFO and DTW.

Pan Am for its part gave up all service from Boston and Chicago across the Atlantic. This meant abandoning Pan Am's BOS-PDL-LIS-CMN and BOS-PDL-LIS-BCN and JFK-PDL-LIS-BCN services. As part of the agreement could still serve it's SJU and MIA to Madrid flights, since Pan Am had never served MAD from either JFK or BOS. So Pan Am effectively pulled out of Barcelona, Casablanca, Lisbon, Paris."

A further route swap, this time between Pan Am and American Airlines, saw AA give up its Australian and South Pacific network and Pan Am swap a variety of Caribbean services. The TWA deal was only temporary and from 1978 some of the routes were reinstated.

The deal was a major success, allowing both Pan Am and TWA to fill their 747s on noncompeting routes. Even better, in 1976 the economy began recovering and travel picked up. Pan Am lost $364 million between 1969 and 1976 but then started to make massive profits again. It looked like Seawell had saved the airline, but of course deregulation was around the corner and the airline's wild ride to oblivion had only just begun. In hindsight the 1970s would have proved to be a disaster for Pan Am no matter what, given the institutional and economic problems it faced, but there is no doubt that the massive outlay on the Boeing 747s almost killed the entire airline. Other US trunk airlines would not fare a great deal better with the big jumbo and this is what I'll explore in part 3.

References

Pan Am 747 Fleet. RZJets.net

Pan Am Fleet. Aeromoes

2006. Pan Am/TWA Deal Of 1975. Airliners.net

1981. Lucas, J. Boeing 747. Jane's Publishing

2012. Gandt, R. Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am

Pan Am Fleet. Aeromoes

2006. Pan Am/TWA Deal Of 1975. Airliners.net

1981. Lucas, J. Boeing 747. Jane's Publishing

2012. Gandt, R. Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am

If you haven't read it I can highly recommend Roberty Gandt's book on the collapse of Pan Am: