Dallas Love Field (DAL): A Tale of Two Cities, of Wrights and Wrongs

Text and airport plan by James C. Kruggel (aka BWI-ROCman from DAC)

Primary Source: A Pictorial History of Airline Service at Dallas Love Field by George W. Cearley, Jr.

Primary Source: A Pictorial History of Airline Service at Dallas Love Field by George W. Cearley, Jr.

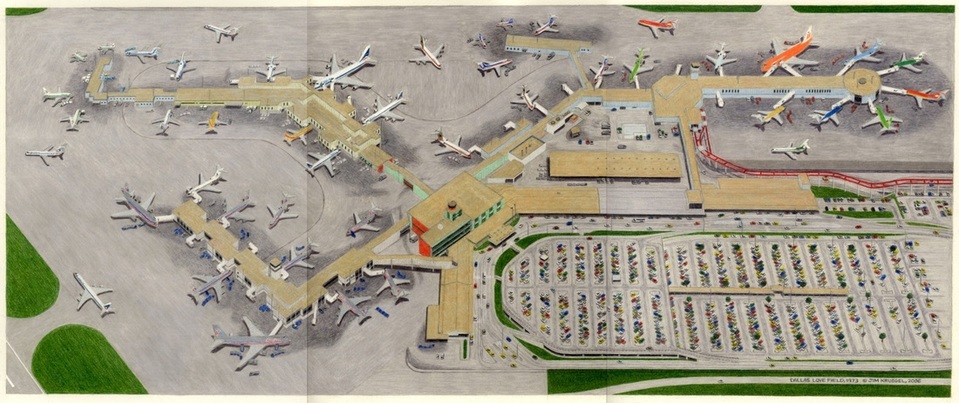

Above: Dallas Love Field in 1973 - see below for close ups of this image

One of the more fascinating airport histories in the United States is of the large city-owned Dallas Love Field (DAL). Dallas, a prominent financial and technical center in North Texas, sits about forty miles east of its smaller neighbor Fort Worth, a financial and agricultural center. The two cities have historically seen each other as something of rivals. Dallas is several times the size of Fort Worth, which saw itself as somewhat in Dallas’s shadow and as more cultured than its business-powerhouse neighbor. Today, the Dallas-Fort Worth “Metroplex” is home to about 6.5 million people, the fourth-largest population center in the United States.

One of the more fascinating airport histories in the United States is of the large city-owned Dallas Love Field (DAL). Dallas, a prominent financial and technical center in North Texas, sits about forty miles east of its smaller neighbor Fort Worth, a financial and agricultural center. The two cities have historically seen each other as something of rivals. Dallas is several times the size of Fort Worth, which saw itself as somewhat in Dallas’s shadow and as more cultured than its business-powerhouse neighbor. Today, the Dallas-Fort Worth “Metroplex” is home to about 6.5 million people, the fourth-largest population center in the United States.

In 1917, the City of Dallas bought 600 acres of land to lease to the Army Air Corps a few miles northwest of downtown, and Love Field was born. The airfield also served as a civilian airport, and in the 1920’s became popular with the performing ‘barnstormers’ who thrilled audiences and promoted flight. The 1926 Air Commerce act helped establish what would become many of the USA’s “trunk” and “local service” passenger carriers in the following decades. In 1928, brothers Paul and Tom Braniff started Braniff Airways at Love Field, and in that decade predecessor-constituent airlines of United and American also started serving Love Field.

In the 1930’s, American and Delta Air Lines entered. Metal propliners such as the DC-3 and Lockheed Electra frequented the airport. In 1940, a terminal opened on Lemmon Avenue, the street which bounded the north side of the airport and went towards downtown. The FAA’s predecessor CAA began operating a control tower in 1941.

After World War II, Dallas grew rapidly and airlines flew new four-engine propliners. The Lemmon Avenue terminal was being outgrown. In 1945 the city began planning for a new terminal complex between eventual parallel paved runways, to be accessed from Mockingbird Lane on the southeast side of the airport. In 1958, the City opened a modern glass-and-steel terminal, clad in colorful green and red spandrels, topped with a five-story control tower, and featuring three concourses for passengers to walk to airplanes. American Airlines offered DAL’s first jet service, Boeing 707’s to New York-Idlewild, in 1959.

|

|

|

|

|

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy landed at Love Field aboard Air Force One, a Boeing 707. He boarded a limousine and rode downtown to greet citizens before a fundraising luncheon. Kennedy was assassinated by former military sharpshooter Lee Harvey Oswald as he rode through downtown Dallas. Vice President Lyndon Johnson was sworn in as President aboard Air Force One at Love Field, and returned to Washington with Kennedy’s body aboard.

At the same time, Fort Worth ran its rival Amon Carter Field / Greater Southwest International airport (GSW) just inside the border of Tarrant County with Dallas County, about 20 miles away. Airlines found that business was much better at Love Field, and Fort Worth’s efforts grow GSW sputtered. Meanwhile, Dallas made numerous additions to Love Field’s terminal as American, Delta, Continental and Braniff grew rapidly with new jets, and local-service carriers such as Trans-Texas / Texas International, Central Airlines, and Ozark also grew. The terminal took on the appearance of a maze during the 1960’s as additions were built in every direction to accommodate the explosive growth of air travel in the first decade of the jet era.

|

|

|

|

|

In 1965, Braniff unveiled “the end of the plain plane,” its splashy series of brightly-colored airplanes and fashionable flight attendant uniforms, that would mark the remainder of its existence. Suddenly, a wide spectrum of colors adorned Love Field. In December 1968, Braniff opened its new ‘terminal of the future’ on the complex’s southeast end. The terminal featured glitzy modern interiors and an overhead “Jetrail” monorail system to bring passengers from the parking lots to the terminal.

|

|

|

|

|

But it was clear that the ongoing explosive growth of air travel, and imminent arrival of jumbo jets, would vastly outgrow Love Field, which was hemmed on all four sides by the City of Dallas, and Bachmann Lake at the northwest border. The Federal Government told Dallas and Fort Worth that they would no longer fund the growth of two airports for the region, and instructed them to find another solution. The cities and local businesses agreed in 1967 to build a gigantic new airport in the prairie between the two cities: Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport (DFW). Construction began, with the new airport set to open in 1974.

Above: DAL's AA (Green), DL (Gold), CO and local service concourses

Below: Braniff's Terminal of the Future

Below: Braniff's Terminal of the Future

During its last few years, DAL was expanded with temporary dog-leg concourse extensions to accommodate passengers. American, Delta, and Braniff all flew massive Boeing 747’s into the airport. Braniff’s famous orange “Great Pumpkin” or “747 Braniff Palace” cast a gigantic shadow over neighborhoods and Bachmann Lake, and served Honolulu daily from DAL. GSW closed in the early 1970’s. Part of one of GSW’s runways is still visible on the southwest end of the DFW property, and American Airlines built its world headquarters on part of the GSW property.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On January 13, 1974, DFW Airport opened, and the vast majority of DAL airline service moved to the monster new prairie airport. But a scrappy little airline begun by lawyer Herbert Kelleher in 1971 was not a signatory to the DFW agreement, and remained at DAL as the law allowed. Southwest Airlines, which flew mustard-colored Boeing 737’s and featured “hot pants” clad stewardesses, offered low fares for flights within Texas. At that time, the only way an airline could escape Federal fare and route regulation was to fly within a state’s boundaries. Competitors failed in court to get Southwest either shut down or evicted from Love Field. The airline grew gradually and prospered at now-quiet Love Field.

In 1978, the United States ended its regime of Federal regulation of fares and routes on interstate air travel. Now any airline could fly any route, and charge any fare it wished. The “trunk” and “local” service carriers, with unions and high fixed costs, saw growth opportunity. But deregulation also brought them danger, from low-cost upstarts. Fort Worth, DFW, and American Airlines saw a competitive threat in Love Field and Southwest. The Majority Leader of the United States House of Representatives, Jim Wright, represented Fort Worth. He added the infamous “Wright Amendment” to a spending bill in 1979, and President Jimmy Carter signed it into law.

The Wright Amendment said that no aircraft larger than 56 seats could fly from Love Field to any airport outside of Texas or its four surrounding states (New Mexico, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana). If an airline wanted to say land in Oklahoma City and continue to Chicago, Wright covered that possibility by including a stipulation that all passengers had to debark the plane at OKC, claim, and recheck their bags.

|

|

|

|

|

For the two decades after USA deregulation, Southwest largely quietly coexisted with the Wright Amendment, while it slowly and carefully grew its network nationwide. Southwest used American Airlines’ old Green Concourse at DAL, and turned the old Delta Gold Concourse into training and hangar facilities. During the 1980’s former Southwest executive Lamar Muse founded his own airline, Muse Air, which succeeded for a few years at DAL before being renamed TranStar in 1987 and shutting down not long thereafter.

But by the mid-1990’s, low-fare Southwest had become a national powerhouse. Congressmen in other states, tired of the high fares from the consolidated legacy carriers, wanted to have Southwest’s low fares to Dallas. In 1997, Congress added the Shelby Amendment, adding Kansas, Mississippi, and Alabama to the Wright perimeter. But Jackson, MS, and Birmingham, AL, the only two markets Southwest added, were not major markets, and the amendment raised little concern. During these decades, American and Continental Airlines occasionally competed with Southwest with flights from DAL to Houston, and Delta attempted outside-perimeter flights with small regional jets. A luxury airline called Legend, using 56-seat all-first-class DC-9’s, tried serving Love in 2000, but quickly failed - partly due to American Airlines aggressively competing against it with specially reconfigured 56 seat Fokker 100s.

|

|

|

|

|

Then, in 2004, Senator Christopher Bond passed the Bond Amendment, which added his home state of Missouri—with its big air markets of Kansas City and Saint Louis—to the Wright perimeter. Fort Worth, American Airlines and Dallas, recognizing that Southwest-hungry Congressmen would now simply dismantle Wright, subsequently asked Congress to stop amending Wright and let them devise a “local solution.” The result was the “Re-Wright”—a five-party agreement signed by Dallas, Fort Worth, American, Southwest, and DFW Airport, and approved by Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2006.

|

|

|

|

|

The “Re-Wright” called for immediate through-ticketing on flights from Love, an end to restrictions on what airports could be served non-stop in October 2014, and a permanent cap on gates at 20. Southwest immediately began serving major markets outside the perimeter in October 2014. Today, court fights continue over the use of the four gates not controlled by Southwest. A new 20-gate concourse was built at Love Field to replace the old 1960’s era gates. After hovering in the 6-8 million passenger range in the 2000’s, Love Field handled 9.4 million passengers in 2014, with only a few months of unrestricted service.

Today, Love Field thrives as a commercial and business / general aviation airport. Southwest has their world headquarters there. The iconic modern 1958 landside building, clad in business-park silver since the late 1980’s, still serves passengers, and the airport’s future is bright. The remaining question is whether the anticompetitive 20-gate limit will remain, as there is strong demand for service from Love Field.