- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

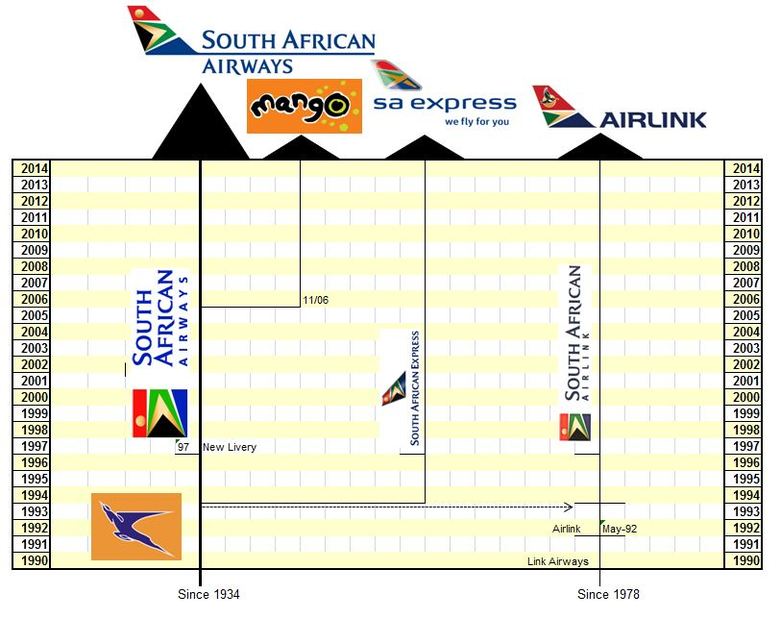

South African Airline Development

1934-1949: South Africa Gets its Wings

From 1934 the air transport environment in South Africa was lightly regulated, though the powerful South African Railways & Harbours Administration (SAR&H) sought to protect their own railway services at the expense of air travel. They purchased several of the existing independent airlines and then at the start of World War Two all civil aircraft were requisitioned, effectively ending the industry's first phase.

During WW2 domestic air services were provided by foreign carriers, like SABENA, BOAC and Southern Rhodesia Air Services, at reasonable rates. This ended postwar when South African Airways (SAA) tookover domestic services and raised all fares by over 25%. Fare reductions were quickly forced upon SAA, but the government continued on a path of regulation and introduced an air traffic policy favouring the national airline for all major domestic routes.

1949-1991: SAA Supreme

Domestic air services within South Africa were regulated in 1949 through the Air Services Act. This remained in force for a period of 41 years. The SAR&H was succeeded by the South African Transport services (SATS), but it was not to be until the late 80s that reform of both bodies was seriously contemplated. This reform was driven by the Margo Commission report in 1984 and the National Transport Policy Study white paper of 1986. It led eventually to the creation of Transnet Limited (the new owner of SAA and other transport companies) in 1989, which had the brief of operating SAA in a more market friendly manner.

It wasn't until 1990 that the Domestic Air Transport Policy was published and in 1991 it became an Act of Parliament effectively deregulating the industry and providing a level playing field for airlines to compete against SAA. There was to be free entry into markets, promotion of choice and competition and the encouragement of private enterprise.

From 1934 the air transport environment in South Africa was lightly regulated, though the powerful South African Railways & Harbours Administration (SAR&H) sought to protect their own railway services at the expense of air travel. They purchased several of the existing independent airlines and then at the start of World War Two all civil aircraft were requisitioned, effectively ending the industry's first phase.

During WW2 domestic air services were provided by foreign carriers, like SABENA, BOAC and Southern Rhodesia Air Services, at reasonable rates. This ended postwar when South African Airways (SAA) tookover domestic services and raised all fares by over 25%. Fare reductions were quickly forced upon SAA, but the government continued on a path of regulation and introduced an air traffic policy favouring the national airline for all major domestic routes.

1949-1991: SAA Supreme

Domestic air services within South Africa were regulated in 1949 through the Air Services Act. This remained in force for a period of 41 years. The SAR&H was succeeded by the South African Transport services (SATS), but it was not to be until the late 80s that reform of both bodies was seriously contemplated. This reform was driven by the Margo Commission report in 1984 and the National Transport Policy Study white paper of 1986. It led eventually to the creation of Transnet Limited (the new owner of SAA and other transport companies) in 1989, which had the brief of operating SAA in a more market friendly manner.

It wasn't until 1990 that the Domestic Air Transport Policy was published and in 1991 it became an Act of Parliament effectively deregulating the industry and providing a level playing field for airlines to compete against SAA. There was to be free entry into markets, promotion of choice and competition and the encouragement of private enterprise.

1991-2000: The Search for Sustained Success

In 1990/91 there were 241,071 aircraft movements and 9,120,900 domestic passengers were transported. This was an increase of over a million from the 1987/88 figures. SAA carried over 90% of scheduled passengers whilst 77% of all passengers had a journey that started or ended in Johannesburg, compared to 44% in Cape Town and 36% in Durban. The primary routes in the nation are still known as the 'Golden Triangle' and consist of Johannesburg-Cape Town, Johannesburg-Durban and Durban-Cape Town.

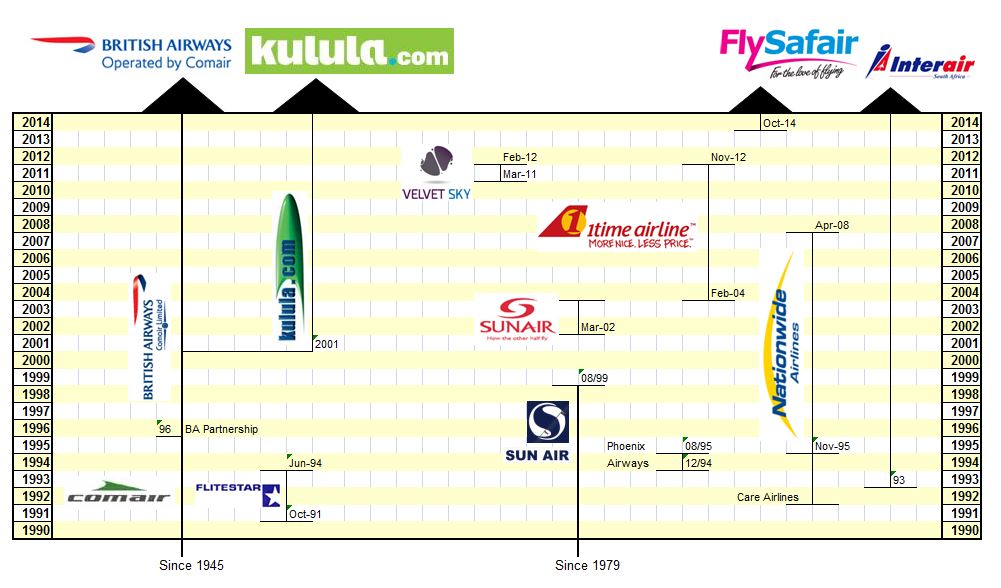

Almost immediately following deregulation in 1991 a series of new and established companies applied for new scheduled rights. The first phase of deregulation saw the creation of several new start up airlines. Flitestar was the first serious contender to SAA. It was a new entrant formed by the long-standing charter carrier Trek Airways. Almost immediately SAA was accused of anti-competitive behaviour and forced to reduce its capacities and increase fares to levels which enabled new carriers to at least gain a foothold in the market. This matter was still ongoing at the time of Flitestar's demise in April 1994, after it racked up losses of over 90 million Rand. Flitestar, competing against SAA with new A320s, though initially successful was not substantially cheaper than SAA and operated a leased fleet which was paid for in USD. This was a significant reason for the carrier's failure after only 30 months.

Following Flitestar's collapse another new airline, Phoenix Airways, began services, this time using elderly Boeing 727-100s. Without the startup capital of Flitestar, unviably low fares, obsolescent equipment and foreign dollar lease payments it survived less than a year.

Three other airlines also joined in competing against SAA up till 2000 and all three of these had more success. Comair had been operating a small collection of scheduled routes since 1945 and was initially careful in entering onto the trunk routes. Instead it kept to its core business of secondary scheduled services and only operated new routes where they could be profitable. It focused on low cost travel and grew heavily between 1992-1997 - from 100,000 passengers per annum to over 1 million. The 1996 signing of an agreement for a franchise operation with British Airways proved to be a shrewd move giving it access to BA's transit passengers, whilst enabling it to have a sound financial base from which to grow.

Sun Air (formerly Bophutsthatswana's Bop Air) began scheduled services on the trunk routes in 1994 and grew quickly with its low fares, high service model so that by 1997 it had a 12.7% share of the market. Despite this it couldn't sustain its operations and was wound up in 1999. Since then there have been at least two other attempts to start companies using the Sun Air name.

Nationwide Airlines also started services in 1995 and by 1997 had a 4-5% marketshare also primarily targeting business travellers using a fleet of BAC One-Elevens and like Comair signing a strategic partnership with a European airline (in this case SABENA of Belgium).

SAA itself had foreseen deregulation since the early 80s and had gradually changed its operations to combat the new entrants introducing such items as business class and a new Frequent flyer programme before 1991. Its takeover of Link Airways (to become SA Airlink) and the startup of SA Express in 1994 additionally enabled it to create feed for its trunk routes and absolve itself of several smaller loss making services. It was widely expected that SAA would be privatised following deregulation but this had still not happenned in 2014. With such a long-standing in the industry, strong existing relationships with airports and suppliers plus the unseen hand of Government ownership it was itself initially somewhat insulated from the worst effects of deregulation to its bottom line.

By late 1996 SAA's marketshare has shrunk to 67% though some of this was due to conscious shedding of loss making regional routes. By the turn of the century of the seven airlines that had potential to challenge SAA's dominance: three had failed, two were in alliance with it and only Comair and Nationwide remained to provide real competition.

In 1990/91 there were 241,071 aircraft movements and 9,120,900 domestic passengers were transported. This was an increase of over a million from the 1987/88 figures. SAA carried over 90% of scheduled passengers whilst 77% of all passengers had a journey that started or ended in Johannesburg, compared to 44% in Cape Town and 36% in Durban. The primary routes in the nation are still known as the 'Golden Triangle' and consist of Johannesburg-Cape Town, Johannesburg-Durban and Durban-Cape Town.

Almost immediately following deregulation in 1991 a series of new and established companies applied for new scheduled rights. The first phase of deregulation saw the creation of several new start up airlines. Flitestar was the first serious contender to SAA. It was a new entrant formed by the long-standing charter carrier Trek Airways. Almost immediately SAA was accused of anti-competitive behaviour and forced to reduce its capacities and increase fares to levels which enabled new carriers to at least gain a foothold in the market. This matter was still ongoing at the time of Flitestar's demise in April 1994, after it racked up losses of over 90 million Rand. Flitestar, competing against SAA with new A320s, though initially successful was not substantially cheaper than SAA and operated a leased fleet which was paid for in USD. This was a significant reason for the carrier's failure after only 30 months.

Following Flitestar's collapse another new airline, Phoenix Airways, began services, this time using elderly Boeing 727-100s. Without the startup capital of Flitestar, unviably low fares, obsolescent equipment and foreign dollar lease payments it survived less than a year.

Three other airlines also joined in competing against SAA up till 2000 and all three of these had more success. Comair had been operating a small collection of scheduled routes since 1945 and was initially careful in entering onto the trunk routes. Instead it kept to its core business of secondary scheduled services and only operated new routes where they could be profitable. It focused on low cost travel and grew heavily between 1992-1997 - from 100,000 passengers per annum to over 1 million. The 1996 signing of an agreement for a franchise operation with British Airways proved to be a shrewd move giving it access to BA's transit passengers, whilst enabling it to have a sound financial base from which to grow.

Sun Air (formerly Bophutsthatswana's Bop Air) began scheduled services on the trunk routes in 1994 and grew quickly with its low fares, high service model so that by 1997 it had a 12.7% share of the market. Despite this it couldn't sustain its operations and was wound up in 1999. Since then there have been at least two other attempts to start companies using the Sun Air name.

Nationwide Airlines also started services in 1995 and by 1997 had a 4-5% marketshare also primarily targeting business travellers using a fleet of BAC One-Elevens and like Comair signing a strategic partnership with a European airline (in this case SABENA of Belgium).

SAA itself had foreseen deregulation since the early 80s and had gradually changed its operations to combat the new entrants introducing such items as business class and a new Frequent flyer programme before 1991. Its takeover of Link Airways (to become SA Airlink) and the startup of SA Express in 1994 additionally enabled it to create feed for its trunk routes and absolve itself of several smaller loss making services. It was widely expected that SAA would be privatised following deregulation but this had still not happenned in 2014. With such a long-standing in the industry, strong existing relationships with airports and suppliers plus the unseen hand of Government ownership it was itself initially somewhat insulated from the worst effects of deregulation to its bottom line.

By late 1996 SAA's marketshare has shrunk to 67% though some of this was due to conscious shedding of loss making regional routes. By the turn of the century of the seven airlines that had potential to challenge SAA's dominance: three had failed, two were in alliance with it and only Comair and Nationwide remained to provide real competition.

2000-2014: Low Cost Comes to South Africa

As in other deregulated markets the growth of the internet has enabled a new generation of low cost airlines to gain marketshare. Comair started South Africa's first with its Kulula offshoot in 2001 and it remains the largest and most successful of the new group.

Nationwide, the other full service independent airline, had less success. It continued to grow and began international services in 2003, however in 2007 a near crash shone a harsh light on its maintenance record and the airline was grounded in November. Though operations restarted, cash-flow problems, high fuel costs and decreasing passenger loads sealed its fate and the airline was liquidated.

This was no doubt excacerbated by the creation of 1Time in 2004 as a second low cost airline. 1Time created a strong network from Johannesburg and Cape Town using MD-80s but folded after 8 years due to a perfect storm of over-expansion, fuel costs, leasing costs and strong competition.

Kulula and 1Time were quickly able to gain 20% of the marketplace but as with most low-cost airlines their model stimulated growth as well as stealing passengers from full service airlines. Another new LCC, Velvet Sky, also started operations, in March 2011, from a Durban base, however it only lasted a year before folding. Despite its short life it was no doubt partly responsible for the demise of 1Time.

The initial benefits that SAA had had over new entrants had gradually been eaten away by 2000 and competition outside of South Africa has further weakened its position, to the extent that by 2014 it was technically bankrupt. It too started its own low-cost offshoot, Mango, in late 2006 however Mango's growth was very conservative with only four aircraft for its first four years. Following the return to an effective duopoly, in 2013, Mango has taken the opportunity to grow its operations.

In July 2013 the airline marketshares in the South African domestic scene were as follows:

1. South African Airways 44.9%

2. Kulula 24.6%

3. Comair 15.5%

4. Mango 15.1%

Continued government financing of SAA has allowed it to stay in operation but perversely ineffective government ownership is also partly responsible for the carrier's dire position. It is clear that it has been partly able to leverage the government's blank cheques to effectively kill off competition (1Time being the most obvious example), however that competition continues to appear with FlySafair just starting operations and others eyeing the domestic marketplace despite its limited size.

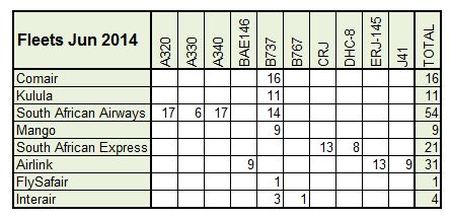

Below is a breakdown of the airline fleets of South Africa in June 2014:

As in other deregulated markets the growth of the internet has enabled a new generation of low cost airlines to gain marketshare. Comair started South Africa's first with its Kulula offshoot in 2001 and it remains the largest and most successful of the new group.

Nationwide, the other full service independent airline, had less success. It continued to grow and began international services in 2003, however in 2007 a near crash shone a harsh light on its maintenance record and the airline was grounded in November. Though operations restarted, cash-flow problems, high fuel costs and decreasing passenger loads sealed its fate and the airline was liquidated.

This was no doubt excacerbated by the creation of 1Time in 2004 as a second low cost airline. 1Time created a strong network from Johannesburg and Cape Town using MD-80s but folded after 8 years due to a perfect storm of over-expansion, fuel costs, leasing costs and strong competition.

Kulula and 1Time were quickly able to gain 20% of the marketplace but as with most low-cost airlines their model stimulated growth as well as stealing passengers from full service airlines. Another new LCC, Velvet Sky, also started operations, in March 2011, from a Durban base, however it only lasted a year before folding. Despite its short life it was no doubt partly responsible for the demise of 1Time.

The initial benefits that SAA had had over new entrants had gradually been eaten away by 2000 and competition outside of South Africa has further weakened its position, to the extent that by 2014 it was technically bankrupt. It too started its own low-cost offshoot, Mango, in late 2006 however Mango's growth was very conservative with only four aircraft for its first four years. Following the return to an effective duopoly, in 2013, Mango has taken the opportunity to grow its operations.

In July 2013 the airline marketshares in the South African domestic scene were as follows:

1. South African Airways 44.9%

2. Kulula 24.6%

3. Comair 15.5%

4. Mango 15.1%

Continued government financing of SAA has allowed it to stay in operation but perversely ineffective government ownership is also partly responsible for the carrier's dire position. It is clear that it has been partly able to leverage the government's blank cheques to effectively kill off competition (1Time being the most obvious example), however that competition continues to appear with FlySafair just starting operations and others eyeing the domestic marketplace despite its limited size.

Below is a breakdown of the airline fleets of South Africa in June 2014:

REFERENCES

Smith, E; 1998. An Evaluation of the Impact of Air Transport Deregulation in South Africa. Rand Afrikaans University

CAPA; 2013. Comair profit recovers on the back of reduced competition and successful transformation programme

CAPA; 2013. South Africa’s Mango, the often forgotten budget airline subsidiary, starts to pursue faster growth

CAPA; 2012. South African Airways and Comair could face new LCC competitor following demise of 1Time

Lubbok Avalanche Journal; 1999: Sun Air liquidated in South Africa

Wikipedia; Nationwide Airlines

Smith, E; 1998. An Evaluation of the Impact of Air Transport Deregulation in South Africa. Rand Afrikaans University

CAPA; 2013. Comair profit recovers on the back of reduced competition and successful transformation programme

CAPA; 2013. South Africa’s Mango, the often forgotten budget airline subsidiary, starts to pursue faster growth

CAPA; 2012. South African Airways and Comair could face new LCC competitor following demise of 1Time

Lubbok Avalanche Journal; 1999: Sun Air liquidated in South Africa

Wikipedia; Nationwide Airlines

- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS