- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

|

November 1990 marked the date that the Australian domestic airline market was finally fully deregulated, however unlike in other markets this did not signal a rollercoaster of new entrant airlines. The Australian market had always been hyper-regulated and even with deregulation the grandfathered airlines, Australian and Ansett, had major advantages. So much so in fact that only a single challenger appeared to compete with them. This was Compass Airlines. Deregulation had been announced on October 31, 1987 giving both Australian and Ansett the opportunity to strengthen their positions prior to the arrival of competition. One of the first things they did was acquire almost all the regional airlines enabling them a stranglehold on feeder routes, whilst Ansett’s acquisition of EastWest allowed it a bulwark with which to compete on leisure heavy routes also.

Other considerations made a new startup look unfavourable. The nationwide Pilots’ Strike of 1989 had resulted in a mass resignation, which had enabled Ansett and Australian to save a fortune in salaries. Worse Ansett and Australian had a stranglehold on the Galileo Computer Reservation System and therefore the travel agent network. In these days before the internet any new airline would struggle to get its message and flights in front of the public. Nonetheless Bryan Grey, who had been part of EastWest, persevered with his new airline, Compass, despite the setbacks and an inability to raise more than $65 million in capital – a figure that even Grey had said was $20 million short of what he thought he needed.

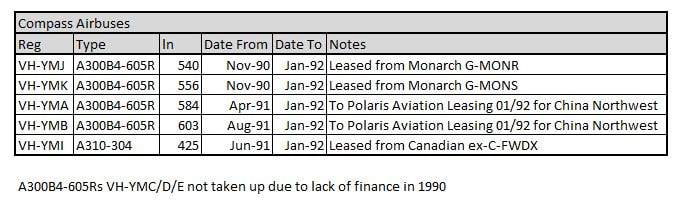

With these restrictions Grey felt he had no option but to use larger aircraft since he couldn’t get the gate space he wanted. His first choice, the 767, was denied to him when the government refused to let Qantas maintain them. The next best option was the larger still A300 but these aircraft were unsuitable as they were expensive to lease, required high load factors to break even, restricted which airports could be operated too plus were fitted out to too high a standard. The latter point was made worse when Compass spent a fortune refitting them to seat 288 in an 8 across config rather than the 360 in 9 across they came with. In hindsight the choice of the A300 was a major error as even with limited gate facilities smaller aircraft could have been turned around more quickly increasing utilisation and would have been a lot more flexible. Faced with a perfect storm of issues Compass ran into another – a major global economic downturn. Passenger volumes should have fallen by 20-30% in 1991 but instead by September it was 37% above that of 1988. This was almost entirely due to the presence of Compass, however obviously in that economic environment it was hard to make a profit even before the incumbent airlines clobbered them with a fare war of enormous ferocity. Compass had said it would be 20% cheaper than the existing airfares but with its first owned A300 arriving in April 1991 the increase in capacity was guaranteed to create a pricing based war. This began in January when Ansett discounted seats by 47-61%. A ceasefire lasted until May but the rest of the year saw escalating fare wars amongst the three majors. It was a boon for customers but could not last. Ansett and Australian were losing a fortune but they had vastly deeper pockets than the underfunded Compass did. Over the period of 1990/91 Ansett lost $200 million, whilst Australian lost $12 million in the first 6 months of 1991. Compass rather creditably lost $16.5 million in its first year but this compared dreadfully to the $20 million profit it expected. Nonetheless by the middle of 1991 Compass had acquired a 10.6% share of the overall market and an impressive 21.3% on just the routes it flew. It had done especially well on the long services to Perth.

The failure of Compass in hindsight seems almost inevitable from day one. It caused a huge public outcry over the percieved unfair nature of the competition used against the airline. Somehow a formal Trade Practices Commission enquiry managed to find no evidence of predatory pricing or misuse of market power. Even if a large part of the airline’s failure can be levelled at Australian and Ansett it remains clear that Compass itself was also to blame. Aside from the A300s the airline’s competitive strategy was muddled, its forecasting errors fantastical, ability to attract high revenue business traffic limited and its yield management poor. As it happened the Compass brand was purchased by a second airline and although it avoided many of the issues that afflicted Compass Mk1 it lasted even less time (only 6 months). The Compass experiment was an expensive mistake given the market conditions, however briefly it provided what has been termed as a ‘one off gift’ to the people of Australia. It would be nearly a decade until real competition appeared in Australia bouyed by the internet age. By then the market had changed massively but the question still remains whether Australia can support more than two airline groups. History to date suggests that it cannot. References

1992. Compass - the popular bankrupt. Greenleft Weekly Douglas E.J. 1993. Airline Competition and Strategy in Australia. Bond Business School Compass Airlines. Wikipedia

2 Comments

explanethings

13/6/2018 11:24:07 am

Despite fairly frequent trips to BNE, SYD & MEL during that period, Compass to me were pretty elusive. I never once saw one of their aircraft.

Reply

Aero kangaroo

13/9/2018 02:20:14 pm

I vaguely remember my only flight with Compass, from Sydney to Coolangatta, I think it was.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm Richard Stretton: a fan of classic airliners and airlines who enjoys exploring their history through my collection of die-cast airliners. If you enjoy the site please donate whatever you can to help keep it running: Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed