- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

|

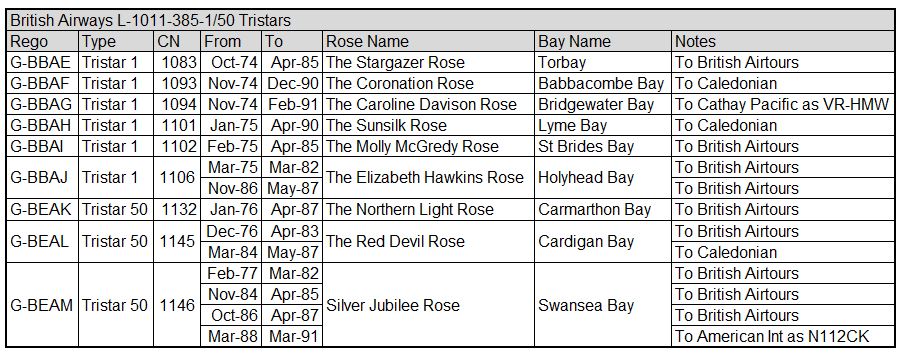

Lockheed's L-1011 Tristar had a long, complicated and varied career with British Airways, and its charter arm British Airtours (later Caledonian Airways). They also had an equally complicated ordering process. Despite, at least initially, lacking the range for longer routes the full-length Tristars served BA well and were at the forefront of making it ‘The World’s Favourite Airline’ during the 1980s.

The original requirement, that would grow into the proposal to purchase Tristars, dated from the early 1960s. Already British European Airways (BEA) was investigating the replacement for its existing airbus, the Vickers Vanguard. As the years past the capacity requirement grew from a 136-seater VC10 derivative named the VC11 to the 200 seat BAC Two-Eleven. BEA was keen on the latter. It was still a narrowbody but offered six abreast seating, however BEA was unable to place an order as the Government instead joined the European Airbus programme, on December 15, 1967, and funding for the Two-Eleven vanished.

BEA never seemed particularly interested in the Airbus project and instead was keen on another possible BAC project – the Three Eleven. This was a wide-bodied design begun in 1968 and designed to carry 245 passengers in an eight abreast layout filling the hole between the 727-200 and L-1011 Tristar. The withdrawal of the UK from the Airbus project in May 1969 looked like it would benefit the Three-Eleven programme and once again BEA was ready to place the launch order if government backing was forthcoming.

Unfortunately, what had looked like a solution to BEA’s problems was once again torpedoed by government policy. The June 1970 election saw the replacement of the left-wing Labour government with a right-wing Tory one a lot less interested in protecting British industry. Worse in the Autumn Rolls-Royce was in such trouble (partly due to the ongoing development of the Tristar engines) that it needed bailing out. On December 3, 1970 the government admitted it could no longer afford the Three-Eleven or to rejoin the Airbus project.

Despite Hawker-Siddeley continuing its involvement in the Airbus A300, using its own funds to design and build the wings, BEA still showed no real interest in the European widebody. Instead with the Three-Eleven dead the airline was allowed to look at US projects. With the Tristar at least using British engines (and ones heavily subsidised by the UK government to boot) it is unsurprising that the big trijet was the selected option.

By this time early a decade had passed and the British Airways board had come into existence, in April 1972. One of the board’s first actions was to place the order for six Tristars, with twelve further options, on September 26, 1972. The order was billed at £60 million for the aircraft and a further £20 million for spares and engines. The Tristar was significantly larger than the mooted BAC Three-Eleven and would be configured in initial BA service with 20 first-class, 300 economy class configuration.

A Tristar appeared in a hybrid Eastern Air Lines, BEA scheme at the 1972 Farnborough Air Show but of course by the time the Tristars were finally ready BEA had ceased to exist and it had been merged into the new British Airways. The Tristars would begin their careers wearing the Negus & Negus livery.

The civil aviation landscape in 1974 had changed massively since the end of the 1960s. The British economy was already weak due to years of strikes and labour disputes when in October 1973 the Arab-Israeli war led to an oil embargo, which led to blackouts and the near collapse of the UK economy. Air travel was, unsurprisingly, massively affected, but somehow BA managed a £16.6 million profit for the year ending March 31, 1974. There was no expectation this would continue and capacity cuts and fuel rationing were introduced, which included removing the earliest Tridents and VC10s from service.

In this environment it might have been seen as unhelpful that the first Tristar was delivered on October 28, however the type represented much improved fuel efficiency over the Tridents, VC10s and 707s. At the same time though BA had allocated £36 million to expenses associated with the Tristar’s service entry. Equipment such as an engine test cell, automatic test gear, an engineering ground simulator, a flight simulator, systems trainer and a passenger cabin mock-up needed to be bought. A further £3.5 million was needed for moveable support items and another £500,000 for outfitting four gates at Heathrow to work with the Tristar.

Unfortunately, service entry was delayed by industrial action. Ramp staff and loaders with the TGWU refused to work with the L-1011 unless paid £5 more a week. They weren’t the only problem as Flight Engineers, The Association of Licensed Aircraft Engineers and BALPA all had grievances too. BA actually only lost £9.4 million in the year 1974-75, less than forecast, although these would increase into the next year when £16.3 million would be lost. It was however estimated that strikes cost the airline £11 million more. The first Tristar revenue service wasn’t until December, when it operated to Malaga under the command of Capt Charles Owens.

All the Tristars were delivered with the Collins triple autopilot, which gave them a full Autoland capability. In fact, the Tristar was the first aircraft to be certified to land in zero visibility and with zero decision height.

The first six Tristar 1s had all arrived by April 1975 but a further three were converted from options and joined the fleet between January 23, 1976 and February 12, 1977. The Tristars initially were used on routes to Malaga, Brussels, Paris, Madrid and Palma. By the summer of 1974 they were also serving Alicante, Amsterdam, Athens, Faro and Tel Aviv. The ongoing impacts of the oil crisis and the worldwide economic recession did have an impact on the Tristars though and some of the original routes no longer warranted the resources of the trijet.

A pair of the Tristar 1s were reconfigured in a 240 seat 2-class, configuration and moved to the BA-OD (Overseas Division) on a three-year transfer from the European division. They were used on routes to the Near and Middle East, primarily to destinations in the Gulf and India.

They were joined by the last two newly delivered aircraft, G-BEAL and BEAM, which arrived in the long-haul configuration. BA had been contracted by Gulf Air to oversee the introduction of their Tristars in 1976, and as soon as the BA-OD saw the economics of operating a -1 to Bahrain, they commandeered the next two Tristars and put them into service competing with Gulf Air. The Bahrain route was at the limit of -1 range, but was doable year-round.

Interestingly the Tristar 1’s lack of range was an inconvenience for BA, although admittedly it had not been purchased with this requirement. The mid-70s downturn meant that the Los Angeles route did not warrant the use of a 747 and yet the alternative, a 707, were load restricted and hardly competitive with Pan Am and TWA widebodies. The Tristar 1s would have been an ideal option if they had the range, but they did not.

Instead BA came to an interchange leasing arrangement with Air New Zealand (NZ), which began on May 1, 1975. Every day an NZ DC-10 flew an NZ service from AKL to LAX. There it was transferred to BA (still in NZ livery) to fly LAX-LHR with BA flight and cabin crew. Another aircraft simultaneously operated in the reverse direction. When the traffic on the LHR-LAX grew so as to warrant the substitution of the DC-10 with a 747 with one year of the interchange leasing agreement still to run BA moved the NZ DC-10s onto the MIA (5-a-week) and YUL (3-a-week) routes while still flying the LHR-LAX route twice a week to supplement their own 747 service and feed the aircraft back into the Air New Zealand fleet. By this time, they were using a quarter of NZ's DC-10 fleet. The agreement came to an end on April 30, 1979.

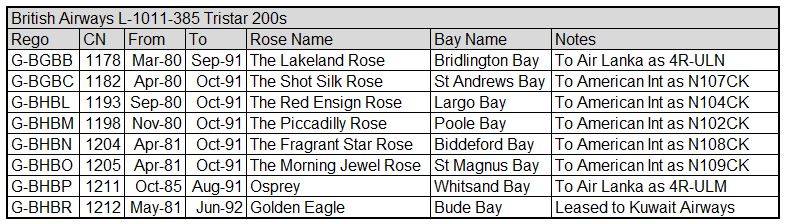

This experience no doubt assisted in the business case for the purchase of Tristar 500s and later 200s. The series 500s will be covered in another post but the series 200s represented BA’s last Tristar orders. The first pair were ordered in January 1979 to assist the new Tristar 500s and allow the return of the last pair of Tristar 1s to European operations (the European and Overseas division Tristars were actually combined into a single fleet in 1978 anyway). By that time BA needed extra Tristar capacity in Europe and as a stopgap leased an Eastern Air Lines Tristar, N323EA, for 20 months from October 1978 to supplement the European Tristar fleet.

In September 1979 a further six Tristar 200s were ordered, with deliveries commencing in late September 1980, at a cost of £127 million. By 1980, as the 707 fleet was wound down, BA wanted to operate the Tristars to the USA and it was discovered that the last three Tristar 1s included extra structural strengthening built into the production line. All BA needed to do to enable transatlantic operations was switch the wheels and axles and the aircraft, designated as Tristar 50s, could carry nine extra tons of payload allowing them the ability to reach the East Coast of the USA.

As well as the Tristar 50s the new Tristar 200s could easily reach the longer US East-Coast destinations, as far south as Miami, plus routes to the Middle-East and Asia. The first series 200 was configured to carry between 250 and 400 passengers and the first, G-BGBB, entered service in March 1980. In 1981 BA modified its livery to only show British titles with the Negus scheme. At the same time the Tristar fleet adopted the names of varieties of Roses, that is except for the last two Tristar 200s, which gained bird names. Into the Landor era these names would be switched for those of Bays but by this time much of the fleet was with its subsidiary British Airtours.

In 1988 British Airtours became Caledonian Airways and gradually most of the Tristar 1s and 50s moved to the charter airline’s fleet permanently. Of the original 9 Tristars only G-BBAG, G-BEAK and G-BEAM did not serve with Caledonian. Still the TriStar 1/50 remained the mainstay of the LHR-CDG route (supplemented by the 757 in later years) until 1989.

By this time BA had made its order for Boeing 767-300s, the first of which joined the fleet in April 1990. The last of the BA Tristars were used on the Manchester and Glasgow to New York JFK service and were retired in October 1991, however at least two aircraft did see some further service. A pair were leased to Kuwait Airways from June to October 1992 following the Gulf War. Having been parked for 8 months they were not particularly reliable apparently. After storage for several years most of the Tristar 200s became freighters with American International.

The Tristars are rather overlooked in BA's history, however they were the mainstay of the high-density European and Middle-Eastern network for over 15 years and the series 200s saw a lot of activity on longer routes during the 1980s. They undoubtedly were a key part in transforming BA from the bolted together, largely unprofitable airline of the 1970s to the streamlined privatised profitable airline of the 1980s.

References

Birtles, P.J. Modern Civil Aircraft 8: Lockheed Tristar Corke, A. British Airways: The Path to Profitability Halford-MacLeod, G. Britain’s Airlines Vol 3: 1964 to Deregulation Woodley, C. The History of British European Airways 1946-1972 BA Tristars fleet exit date. PPRuNe

3 Comments

Michael Hardesty

17/2/2020 06:50:24 pm

I was at the 1972 Farnborough airshow. When we drove in and saw the massive Tristar we were amazed especially having the BEA logo. At the time we were used to only seeing Tridents & VC10s. I have this model on my study windowsill, it was a one off. As usual your post is very good & informative.

Reply

Gary Frey

19/2/2020 04:40:48 pm

Looking for information on the British L-1011-500's. Specifically, EGLL-KMSY route/schedules/history.

Reply

Tom Seeberg

3/7/2021 03:00:56 pm

I have flown on some of these aircrafts back in 1989 in january. I flew the route LHR- BAH- BKK and the same back. The route all together was LHR-BAH-BKK-KUL. I can remember they had bigger windows than Boeing ac. It was a great plane but had to short range and they where not actually longrange. Still they was great with big softy seats in red color in 1989

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm Richard Stretton: a fan of classic airliners and airlines who enjoys exploring their history through my collection of die-cast airliners. If you enjoy the site please donate whatever you can to help keep it running: Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

![British Airways Tristar brochure - front page [cover]](https://live.staticflickr.com/5230/5603750891_c67c5e70e5_c.jpg)

![British Airways Tristar brochure - back page [rear cover]](https://live.staticflickr.com/5063/5603754133_16e9f97cda_c.jpg)

![British Airways Tristar brochure -centre [map]](https://live.staticflickr.com/5224/5606103542_f0ea56de38_z.jpg)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed