- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

|

The Convair 990 was an unmitigated disaster for the Convair Division of General Dynamics. A product of a misguided attempt to compete against Boeing and Douglas, which led to almost suicidal behavior from the manufacturer in selling a paper aeroplane on staggeringly unfavourable terms. American Airlines, the launch customer barely wanted the aircraft but nonetheless the 990 proved strong and reliable in service. Sadly, this was not enough to save its career at AA.

I have written about the Convair 990 a few times previously. To see those posts go here:

The loss of the United Airlines order for 30 Convair 880s in 1957 left Convair desperate to sell its wares to American Airlines. So desperate in fact that Convair was willing to make major modifications to its 880 and sign a contract without really knowing what is was building or how it could be done. C.R Smith’s American Airlines wanted to fly an all first-class “Blue Streak” service coast-to-coast, which would be at least 45 minutes faster than the early 707s of TWA and DC-8s of United. American had also ordered 707s but was planning on flying them mostly in coach configuration. It would be the Convair 600, as it was called at the time, that would give it a competitive edge.

American placed an order for 25 aircraft, with 25 further options, in November 1958. At the same time it ordered 25 of Boeings 720, which had been stealing 880 orders away from Convair for some time. Somehow the contract was signed without approval from the board at General Dynamics. Presumably if they’d have seen it they’d have killed it, since it promised an almost entirely new aircraft and pushed the envelope of what was technically possible.

Built into the contract with American were performance guarantees the most optimistic of which was the required ability to fly at 635 mph nearly 100 mph faster than other jets. That wasn’t all as the 990 needed to be able to fly between La Guardia and Midway both of which had short runways.

C.R Smith really took Convair to town with the contract, understanding all too well how desperate Convair was. The first 25 Convairs only cost him $100 million and instead of a cash down-payment Convair agreed to accept 25 DC-7s at $22.8 million, over double their market value. This left the individual aircraft purchase price at just over $3.5 million.

Even if Convair could have met the performance guarantees they would not have been making a profit on the AA deal and would have needed a far longer production run than the eventual 37 units to see any return on investment. Follow on sales were hard to come by even prior to the aircraft’s first flight. Both Continental and Pan Am opted for Boeing 720s. Only SAS and Swissair signed up for new Convairs.

To meet the performance guarantees the Convair 600 was the first aircraft designed around a turbofan engine – the General Electric CJ-805-23. It also gained the unique overwing anti-shock bodies designed to decrease drag at high subsonic speeds. Unfortunately, although GE was considered to be ahead in the turbofan game Pratt & Whitney came from behind and stole a march with its own turbofan JT3D engines. These were flight testing before the 600’s first flight. Even worse, Pratt found a way to upgrade the turbojet JT3Cs into turbofans. C.R. Smith promptly upgraded his entire Boeing 707 and 720 fleet to turbofans. Not only did this render the 600’s mission effectively obsolete but it killed the chance for new orders.

At least the Convair 600 got a cool new name. In August 1960 it was announced that the name had been changed to the Convair 990. This was at American’s behest as they didn’t want it to be seen as inferior to the 880. Sometimes it is suggested the 990 relates to the cruising speed of 615 mph in km but at the time 635 mph was still the target. Flight testing of the first six production 990s began on January 24, 1961 but almost immediately serious issues were encountered with turbulence and outboard engine oscillation. Fixing these issues caused an initial six-month delay but further problems arose and it was clear the 990 would never reach its potential. Maximum speed could only be reached at the cost of excessive fuel burn. Even at only 584 mph transcontinental range was not assured.

Convair went back to American and frankly it would probably have been better for General Dynamics if the entire order had been cancelled and the 990 programme scrapped. American found itself in an intriguing position. It had Convair over the barrel but at the same time was desperately short of aircraft. In a revised agreement, signed on September 21, 1961, its order was cut to 20 frames and the options cancelled. The original deal had already been financially advantageous to AA but this one was even more so. AA would receive the first 15 frames unmodified and discounted $300,000 each no later than June 30, 1962. Convair still would need to improve the 990’s performance to at least 620 mph by the next February or AA would return all the aircraft and walk away. If the speed could be met it would take the last 5 aircraft of the order.

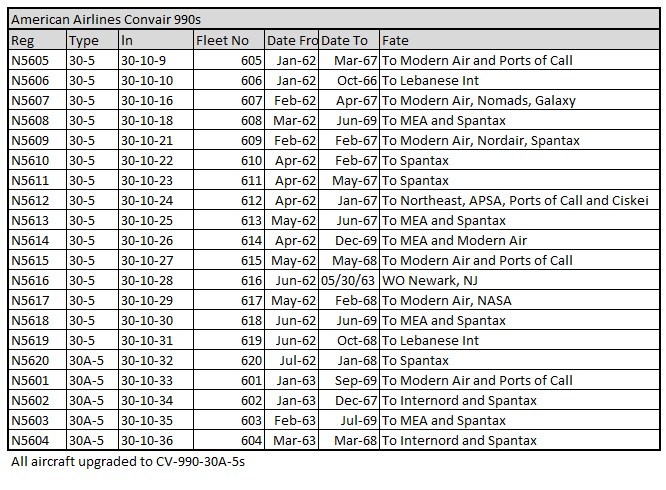

The result of this was that American received its first 990s and put the type into service on March 18, 1962 between New York Idlewild and Chicago O’Hare. The 990s it received were in the end no faster than the Boeing 707s it already operated. Convair was eventually able to resolve many of the 990’s issues and the CV-990A was born, but only six were built, five of which were the extra American frames.

In the end the 990 concept, even at its original design, was flawed. Fuel consumption would have been almost double that of economical flight levels for a small speed advantage. Plus, the speed was only really attainable at 21,500 feet, way too low for most longer routes. In the end the 880/990 programme was a staggering loss for General Dynamics - $425 million in the early 60s. This equated to an average of $4.16 million per plane - more than the purchase price! On the plus side the 990 prove to be super-strong and reliable in service.

American Airlines got its 990s but by that time had been operating turbofan 707 and 720s for over a year. Originally AA was going to fit the type out in a 92 seat one-class layout complete with a six-seat lounge. This was long forgotten by the time the 990s were deployed on medium range routes. Instead they were fitted with a 42 first class and 57 coach configuration with a smaller four seat lounge. Later the ratio was modified to 34:67.

Convair just met its delivery promise for the first 15 frames with the last arriving on June 29. They proved useful extra jet capacity and AA agreed to take the extra five frames in 1963. All 20 aircraft were upgraded to CV-990As by the end of 1964, the work being carried out by AA at its Tulsa facility.

The Convairs were also the first aircraft in the fleet to be called Astrojets and not to carry Flagship names. The Astrojet name was a marketing success. It went hand in hand with the new AA livery cruelly nicknamed the ‘Squashed Egg’ by some employees. The new scheme first appeared on the new Boeing 727s and almost immediately the trijets spelled the end of the 990s.

In 1965, as 727 deliveries accelerated, it was decided to start selling off the 990s. The first two aircraft were sold in October that year and January 1966 to Lebanese International Airlines. It was another year before the next 990s were sold but the drawdown continued swiftly thereafter. The last CV-990s flew for American at the end of October 1968. One of the last routes flown by the type was the 2,143 mile New York to Phoenix segment. This was also about as close to a transcontinental route as the 990 ever got.

Selling on the 990s proved a complicated task for American due to the failure of the Swedish charter airline Internord and a buyback deal with MEA for 720s. None of the returned aircraft ever flew with AA again and the last aircraft was sold to Spantax in May 18, 1972. Spantax of course got great use out of the aircraft:

References

Proctor, J. Convair 880 & 990. Great Airliners Series Vol 1 1985. Serling, R. Eagle: The Story of American Airlines. St Martin's Marek

3 Comments

John Adkins

28/6/2020 09:25:03 pm

The costumed man holding the horn and the "Royal Coachman" sign at the rear door of a 990 was Eddie Nugent, an actor who was hired by AA in 1957 to publicize its Royal Coachman service, first on its DC-7Bs and later on its jets.

Reply

Miles W. Rich

31/3/2021 06:27:01 pm

Pan Am never ordered 720 or 720Bs from Boeing. They bought 6 used ones from Lufthansa and 3 from American. American never took the five additional 990As.

Reply

Richard Stretton

31/3/2021 06:52:45 pm

Indeed. I did say Pan Am 'opted for' not ordered 720s. I also never said they took all 25.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm Richard Stretton: a fan of classic airliners and airlines who enjoys exploring their history through my collection of die-cast airliners. If you enjoy the site please donate whatever you can to help keep it running: Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

- Home

-

My Models

-

AV History

- Airline History Blog

-

Airline Development

>

-

Liveries

>

- Aeroméxico Liveries

- Air China Special Liveries

- American Airlines Liveries

- British Airways Liveries

- Continental Airlines Liveries

- Delta Air Lines Liveries

- Eastern Air Lines Liveries

- Landor Liveries

- National Airlines Liveries

- Northeast Airlines Liveries

- Northwest Airlines Liveries

- Pan Am Liveries

- Trans World Airlines Liveries

- United Airlines Liveries

- Western Airlines Liveries

- Airbus A380s >

- Boeing 747 >

- Real Airport Histories >

- Plane Spotting >

- Aviation Stickers >

-

1:400 SCALE

- Collecting 1:400 Scale >

- The History of 1:400 Scale >

-

1:400 Brands

>

- Aeroclassics >

- Airshop Diecast

- AURORA Models

- Aviation400 (2007-2012)

- Big Bird 400 Your Craftsman

- Black Box Models

- Blue Box & Magic Models

- C Models

- Dragon Wings

- El Aviador 400

- Gemini Jets >

- JAL Collection / Jet Hut >

- Jet-X >

- MP4 Models

- NG Models >

- Panda Models >

- Phoenix Models >

- Seattle Models Co (SMA)

- Skyjets400

- Sovereign Models

- TucanoLine

- Witty Wings / Apollo

- Yu ModeLs

- 1:400 Custom Models >

- Production Numbers

- Zinc Rot

-

1:400 Moulds

- The Best Moulds >

- Airbus >

-

Boeing

>

- Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser

- Short Boeing 707s & 720s

- Boeing 707-320/420

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 727-100

- Boeing 727-200

- Boeing 737-100/200

- Boeing 737-300 >

- Boeing 737-400

- Boeing 737-500

- Boeing 737-600

- Boeing 737-700/800/900 >

- Boeing 737 MAX

- Boeing 747-100/200 >

- Boeing 747-400 >

- Boeing 747SP

- Boeing 747-8 Interactive

- Boeing 747LCF Dreamlifter

- Boeing 757-200 >

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200

- Boeing 767-300

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300

- Boeing 787

- British >

- Douglas >

- Lockheed >

- Other >

- Chinese >

- Soviet >

- Smallest Moulds in 1:400

-

1:400 Reviews

-

Model News

- Model Blog

-

New Mould Samples

>

- Aviation400 >

- JC Wings >

-

NG Models 400 Scale

>

- Airbus A318

- Airbus A319/320 CEO

- Airbus A319/320 NEO

- Airbus A321CEO & NEO

- Airbus A330-200/300

- Airbus A330 Beluga XL

- Airbus A330-800/900

- Airbus A340-200/300

- Airbus A350-900

- Airbus A350-1000

- Boeing 737-600/700/900

- Boeing 737-600 Refresh

- Boeing 737-800

- Boeing 737 MAX-8/MAX-9

- Boeing 737 MAX-7/MAX-10

- Boeing 747-100

- Boeing 747-200

- Boeing 747-400

- Boeing B747SP

- Boeing 747-8I

- Boeing 747-8F

- NG 747s Together

- Boeing 757-300

- Boeing 767-200/300 >

- Boeing 767-400 >

- Boeing 777-200

- Boeing 777-300/300ER

- Boeing 787-8

- Lockheed L-1011 Tristar

- Lockeed Tristar 500

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-87

- Tupolev Tu-154

- Tupolev Tu-204/Tu-214/Tu-234

- NG Models 200 Scale >

- Phoenix Models >

- Yu ModeL >

-

1:600 SCALE

- DIORAMAS

RSS Feed

RSS Feed